Next: Example: Deflection of a Up: Noninertial Frames of Reference Previous: Motion Near the Earth Contents

Tidal forces are due to the the variation of the effective force with position. The tides seen in the earth's oceans are primarily caused by the moon with a significant additional effect from the sun.

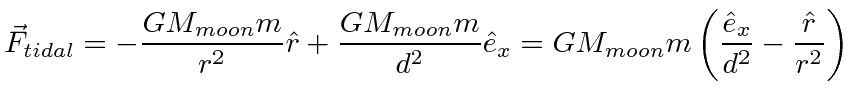

Let us deal with the

tidal forces from one body, the moon, first.

With the earth in free fall, the effective force due to acceleration exactly cancels the gravitational attraction

at the center of the earth, but, the force of gravity varies with position, while the acceleration of the earth does not.

Thus, the remaining effective force comes from the difference between the

gravitational attraction of the moon at some position

![]() and the gravitational attraction of the moon

at the center of the earth.

and the gravitational attraction of the moon

at the center of the earth.

Lets

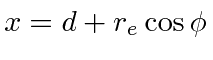

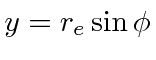

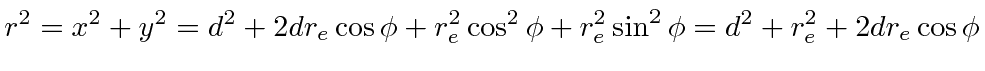

set up a coordinate system.

Put the moon at the origin with the center of the earth at a distance

![]() along the

along the

![]() axis.

We can put the point at which we are evaluating the force in the

axis.

We can put the point at which we are evaluating the force in the

![]() plane without loss of generality.

As usual, call the angle from the

plane without loss of generality.

As usual, call the angle from the

![]() axis

axis

![]() Let the radius of the earth be

Let the radius of the earth be

![]() and of course, the vector from the center of the moon to the point

at which we are evaluating the tidal force can be

and of course, the vector from the center of the moon to the point

at which we are evaluating the tidal force can be

![]() .

.

|

||

|

||

|

||

![$\displaystyle \vec{a}_{tidal}=GM_{moon} \left[{\hat{e}_x\over d^2}-{\left(d+r_e...

...t(r_e\sin\phi\right)\hat{e}_y\over (d^2+r_e^2+2dr_e\cos\phi)^{3\over 2}}\right]$](img247.png) |

||

![$\displaystyle \vec{a}_{tidal}=GM_{moon} \left[\left({1\over d^2}-{\left(d+r_e\c...

...t{e}_x -{r_e\sin\phi\over (d^2+r_e^2+2dr_e\cos\phi)^{3\over 2}}\hat{e}_y\right]$](img248.png) |

||

![$\displaystyle \vec{a}_{tidal}={GM_{moon}\over d^2} \left[\left(1-{1+{r_e\over d...

...phi\over (1+{r_e^2\over d^2}+2{r_e\over d}\cos\phi)^{3\over 2}}\hat{e}_y\right]$](img249.png) |

||

![$\displaystyle \vec{a}_{tidal}\approx{GM_{moon}\over d^2} \left[\left(1-{1+{r_e\...

...1+3{r_e\over d}\cos\phi)}\right)\hat{e}_x -{r_e\over d}\sin\phi\hat{e}_y\right]$](img250.png) |

||

![$\displaystyle \vec{a}_{tidal}\approx{GM_{moon}\over d^2} \left[\left(1-\left(1-2{r_e\over d}\cos\phi\right)\right)\hat{e}_x-{r_e\over d}\sin\phi\hat{e}_y\right]$](img251.png) |

||

![$\displaystyle \vec{a}_{tidal}\approx{GM_{moon}\over d^2}{r_e\over d} \left[2\cos\phi\hat{e}_x-\sin\phi\hat{e}_y\right]$](img252.png) |

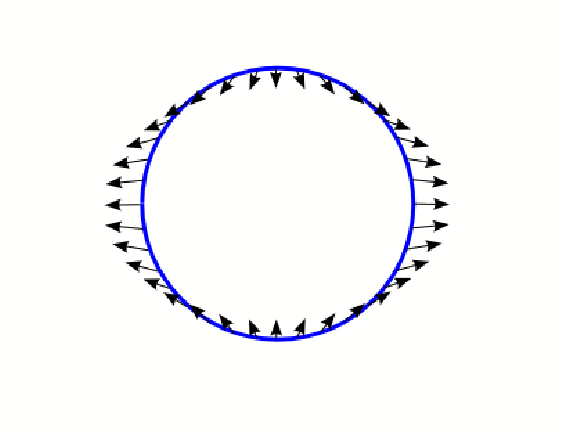

After computing the tidal acceleration fully, we have approximated it to

first order in

![]() to make it easier to see what the primary effect is.

The tidal force is proportion to the

inverse cube of the distance.

The positive cosine term in the

to make it easier to see what the primary effect is.

The tidal force is proportion to the

inverse cube of the distance.

The positive cosine term in the

![]() direction tends to pull the earth apart,

while the negative sine term tends to squeeze it together in the

direction tends to pull the earth apart,

while the negative sine term tends to squeeze it together in the

![]() direction.

The tidal acceleration is shown in the figure below.

direction.

The tidal acceleration is shown in the figure below.

Its easy to see that there are two high tides and two low tides per day.

What really happens to the ocean and to the earth is complicated. The earth is not solid and can be deformed even if not covered by water. To create a high tide, a lot of water has to move which takes time. Its not surprising that the horizontal component of the tidal acceleration plays an important role. With that component potentially pushing water up against land, the height of tides is not simple to calculate. Of course, we do it well by now, but there are a lot of effects, including the deformation of the ``solid'' parts of the earth that must be understood. The time it takes for a wave (say due to the horizontal acceleration) to propagate half way around the earth is about 30 hours, while the high tides are every twelve hours. In most places there is a delay between the phases of the Moon and the effect on the tide. Springs and neaps in the North Sea, for example, are two days behind the new/full Moon and first/third quarter. This is called the age of the tide.

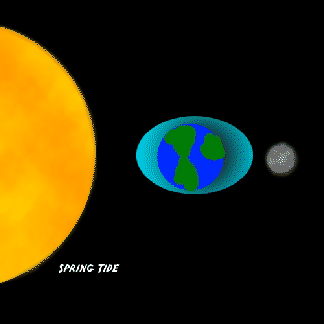

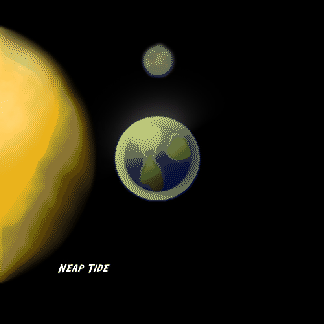

Nevertheless, we can understand the basic ocean tides rather simply. First of all we have to combine the effects of the moon and the sun. The lunar tide should be about twice as big as the solar. When the moon and the sun line up, at new and full moons, the tidal accelerations add, causing very high and low tides (spring tide). When they are at 90 degrees, they tend to cancel (neap tide).

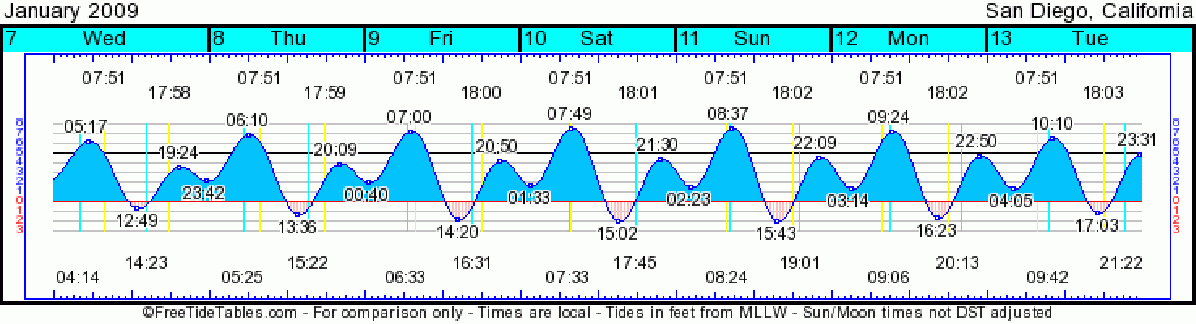

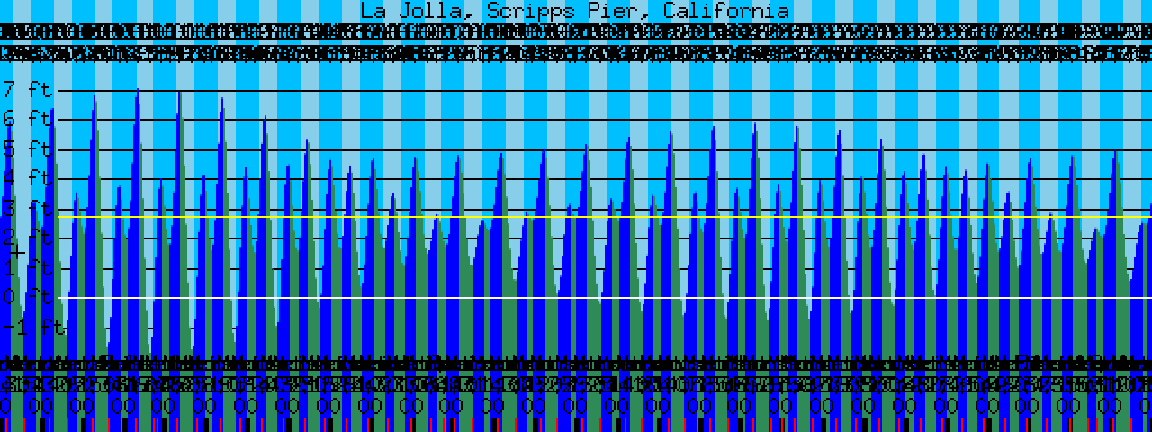

The two tides of the day can differ significantly in height in La Jolla (for example),

if the sun (or moon) is in the southern hemisphere,

because we can get closer to having

than we can to

than we can to

.

The two plots below show the La Jolla tides in two time scales.

.

The two plots below show the La Jolla tides in two time scales.

One can see several periods of oscillation of the highest and lowest tides.

If the earth didn't rotate and the continents didn't move under the tidal forces, one could compute the height of the tides by finding equipotential surfaces. This at least gives an order of magnitude estimate of the height of the tides. Its done in Taylor and we find.

Many famous physicists and mathematicians worked on the problem of the tides. Isaac Newton laid the foundations for the mathematical explanation of tides in the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687). In 1740, the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris offered a prize for the best theoretical essay on tides. Daniel Bernoulli, Antoine Cavalleri, Leonhard Euler, and Colin Maclaurin shared the prize. Maclaurin used Newton's theory to show that a smooth sphere covered by a sufficiently deep ocean under the tidal force of a single deforming body is a prolate spheroid with major axis directed toward the deforming body. Euler realized that the horizontal component of the tidal force (more than the vertical) drives the tide.

In 1744 Jean le Rond d'Alembert studied tidal equations for the atmosphere which did not include rotation. The first major theoretical formulation for water tides was made by Pierre-Simon Laplace, who formulated a system of partial differential equations relating the horizontal flow to the surface height of the ocean. The Laplace tidal equations are still in use today. William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, rewrote Laplace's equations in terms of vorticity which allowed for solutions describing tidally driven coastally trapped waves, which are known as Kelvin waves.

The tides can be quite complex but it is worth studying the basic phenomenon of tides.